Investors are starting to believe in the Turkey U-turn story, a little.

Flows into the country’s equity markets turned positive in November and hit more than $1 billion a week in December, according to researcher GlobalSource Partners. Yields on benchmark 10-year dollar bonds have dropped 200 basis points in the past two months, to about 7%. Central bank currency reserves have swelled 40% from a trough this summer.

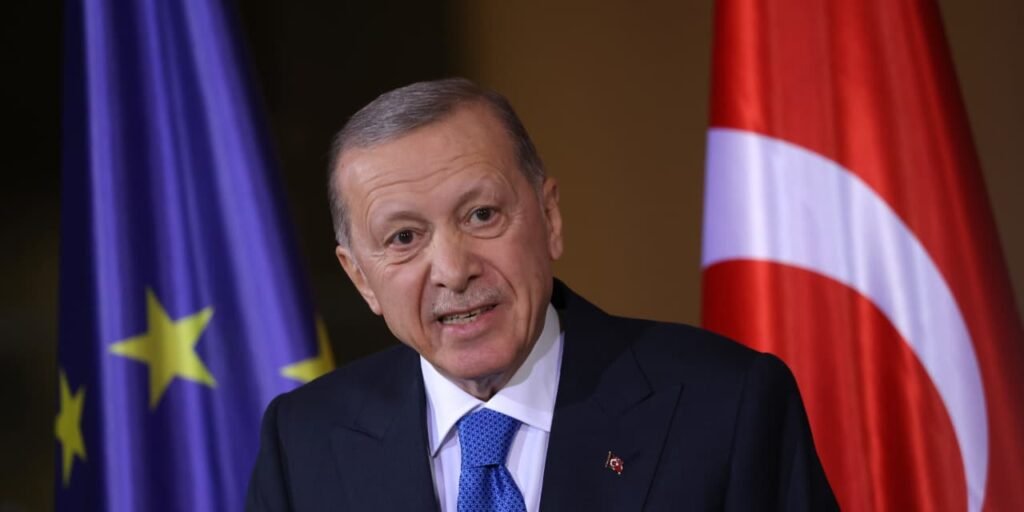

Catalyzing these good vibes is the economic policy surprise of the year: Turkish leader Recep Erdogan turning orthodox after his re-election as president in May. Erdogan the campaigner scorned any thought of austerity even as annual inflation in Turkey rocketed to 80%. He insisted that high interest rates cause inflation, whereas Economics 101 teaches the opposite.

In June, he brought in a new central banker, Hafize Erkan, who has hiked rates from 8% to 42.5%. Economists expect one more increase, to 45%, in January. She and finance minister Mehmet Simsek, a former investment banker who is also a market favorite, have been hacking away at regulations that steered subsidized credit to favored borrowers.

Six months on, Erdogan’s conversion is looking like it might have legs. “I think Erdogan understood the seriousness of the inflation situation,” says Emre Akcakmak, a senior consultant at East Capital. “We are largely back to orthodox policy.”

Whipping Turkish inflation is a multiyear task, however. The central bank projects it can reach single digits only in 2026. Even that target could be overly optimistic. “Inflation may prove stickier than envisioned,” says Murat Ucer, GlobalSource Partners’ Turkey economist.

There’s little faith that Erdogan, a prime-the-pump populist for most of his two decades in power, will stay such an arduous course. The lira has lost nearly 95% of its value over the past 10 years.

“I don’t want to be around for when the orthodox policy becomes really painful,” says Edward Al-Hussainy, head of emerging market fixed-income research at Columbia Threadneedle Investments. He is holding on to Turkish hard-currency bonds anyway, figuring the reform pivot will lure back investors who have fled the market, for a while longer. “This is a very under-owned name,” Al-Hussainy says. “We’re probably about two-thirds of the way through the asset price adjustment.”

The calculus for equity investors is more complex. The

iShares MSCI Turkey

exchange-traded fund has dropped 15% since Oct. 1, erasing a bull run after Erdogan first brought in the Erkan-Simsek dream team. The epic central bank hikes have increased bank deposit rates to around 50% annually, pulling local investors out of the stock market, Akcakmak says.

He’s still bullish on consumer staples companies, which should gobble market share as tight money forces Turks into frugality. Top names in this category—discount retailer

BIM Birlesik Magazalar,

brewer

Anadolu Efes,

and

Coca-Cola Icecek

—have kept rallying while the market index sagged.

Domestically facing companies are on the right side of shifting macroeconomics, adds David Aserkoff,

J.P. Morgan’s

equity strategist for emerging Europe and the Middle East. Their earnings should at least keep pace with inflation, which J.P. Morgan still sees at 40% by the end of next year, while the lira declines 17%. That means a boost to profit in dollar terms. Exporters will suffer from the reverse logic, as costs grow faster than revenue. “The sweet spot right now is in domestic staples,” he says.

A broader argument for Turkish stocks rests on valuation and positioning. Turkey is dirt cheap relative to other emerging markets, at an average price-to-forward-earnings ratio of 3.9, and somewhat cheap relative to its own history, Akcakmak figures. “This is the fifth time over the past 15 years that we have been close to these levels, and every time we have seen a bump,” he says.

Foreign ownership of Turkish equities has fallen by half over the past four years, Aserkoff adds, setting conditions for a rebound. “The story of 2024 will be foreign investors moving into the market,” he says.

That is, of course, if Erdogan doesn’t change his mind again. Having steadily defanged parliament, the judiciary, the central bank, and the press, the president can shift course for his nation of 86 million pretty much at will, and he does. Some investors won’t buy into that at any price. “There’s a long record of institutional degradation affecting every branch of government,” says Samy Muaddi, portfolio manager for emerging market bonds at

T. Rowe Price.

Turks themselves are hopeful but scarred, Akcakmak says. “This is one of the most resilient countries,” he says. “But with a completely different environment every year, people are quite tired.”

Write to editors@barrons.com

Read the full article here